When should I add dry hops?

Dry Hopping

If you’re ready for your beer’s hop nose to wow you, it might be time to try dry hopping.

Dry hopping is the process of adding hops to beer after fermentation has begun. Dry hopping conveys a fresh hop aroma in the beer without adding any bitterness and brings a unique taste character.

Adding hops later on in the process conserves the flavor and aroma from the hops’ oils. These are different from the alpha acids that provide the beer its bitterness. The oils add no bitterness, just flavor, and aroma. During the boiling process, nearly all the hop oils evaporate; the longer the boil time, the more oils will be lost. The hops put in at the start of the boil for bittering lose virtually all of their oils. Hops added near the end of the boil do not lose as much oil but still, lose a good deal. And the heat of the boil causes chemical changes in the oils, even those that remain lack the aroma of fresh hops.

So, if we wish to add hops to provide a fresh hop aroma to the beer, when is the best time to do it? Generally, dry hopping was done in the serving cask. A charge of fresh hops would be included in the cask right before the bung was hammered in. If you keg your beer, you could add the hops to the keg. This gives the beer the best and a fresh aroma. But what if you bottle? It makes sense to take a step backward in the process and add the hops to the fermenter. But there is a right time and a wrong time to do it.

The Right Time

The best time to insert the hops into the fermenter is just as the fermentation begins to slow down. This is usually obvious by the head (or kraeusen) starting to diminish, which usually corresponds with a decreased bubbling in the airlock. Typically, this will be three to four days after fermentation has started. If you are using a single-stage fermenter, just add the hops. If you use a secondary fermenter, rack the beer now and add the dry hops to the secondary.

The wrong time to add the hops is at the very beginning of fermentation or close to it. Hops are not a sterile product, and placing them in too soon can cause contamination in your beer.

If you wait for the right time, various factors are at work in your favor. The beer’s pH will have dropped to the point where the organisms on the hops can’t survive, and the alcohol now present also helps to kill them. You also have a healthy yeast population in your beer, and this yeast will has tendency to starve out the other organisms. There is no danger of contamination from dry-hopping if you do it at the right time.

The last good reason for the wait is that during the initial stages of fermentation, large quantities of CO2 are created, and this will scrub the hop aroma right out of your beer.

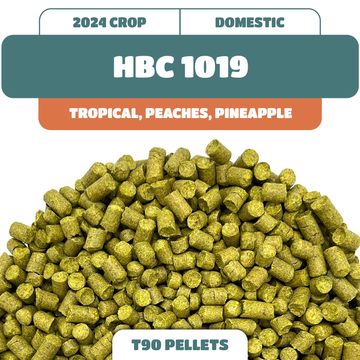

Pellets or Whole Hops?

How you dry hop depends on what kind of hops you are using (pellets or whole) and where you are dry hopping (keg or fermenter).

As far as dry hopping goes, there are some major differences between using pellets and whole hops. Pellets primarily float on the surface but eventually settle to the bottom. Whole hops float on the surface nearly all the time.

The hop oils are found in the hops’ lupulin glands. These have been broken in pellets but are mostly intact in whole hops. All of the hop oils can get into the beer almost instantly with pellets and may take a week or two to get a decent amount of oils released when using whole hops.

One note about pellets: Sometimes, adding pellets may seem to kick fermentation into a higher gear for a while. While this is sometimes a consequence of stimulating the yeast when stirring in the pellets, it is most likely just CO2 being released. The pellet particles become thousands of bubble nucleation points and cause lots of CO2 to come out of the solution. So be sure you are prepared for this!

Fermenter or Keg?

Let’s look at the fermenter case first. If you are adding pellets to the fermenter, they will sink to the bottom sooner or later. The hop oils will be distributed into the beer in a few days, usually by the time the hops have settled out. All that you must do is thoroughly rack the beer off the yeast and hop sediment. A rule of thumb is to leave the pellet hops in the beer for at least a week before bottling. This gives them time to settle and time for the aroma to become infused.

If you want to add the hops to the keg, you’ll certainly want to contain them somehow. If you’re using pellets, a bag-and-weight system is ideal. Otherwise, you’re going to keep pulling pellet particles through the dip tube, and they’ll surely clog the keg connectors. If you are using whole hops, you can use nearly any fine mesh bag, but don’t pack the hops too tight. You would like to have the beer blend in with the hops. Be sure to weigh it somehow. One useful tip is to wedge the bag between the keg wall and the dip tube, as near to the bottom as possible.

If you use pellets, you’ll note that the hop aroma and flavor in the beer can be overwhelming initially. Because the lupulin glands are burst, all the oil goes into the beer at once. Be patient, and it will mellow out. Then again, since the beer is usually cold, the hop oils are released very slowly from whole hops when they’re in the keg. This acts as a time-release effect and keeps the aroma level reasonably constant over time.

How Hoppy?

How much hops to use when dry hopping is dependent on a lot of factors, like nearly everything in brewing. How hoppy do you like your beer? What kind of hops are available? What is their oil content? Where are you dry hopping? How much time do you have? What is the temperature?

You must determine on your own how hoppy you like your beer. Some hops have a more powerful or distinctive aroma than others. This is linked in part to the amount of oil they contain and a particular variety’s aroma profile.

Feel free to experiment – there aren’t any rules for what varieties you can use, and you might just create a new style! In the US, the most popular hop for dry hopping is Cascade. But you can use any hop with a decent aroma. The newer high-alpha hops are currently being used plenty these days, with Centennial and Columbus leading the list. If you can, smell the hop while it’s fresh. If you can imagine that aroma in your beer, do it! You can also experiment with mixing varieties.

Temperature also plays an important part in the quality and strength of the hop aroma. Warmer temperatures extract more oils than colder temperatures — this is particularly noticeable with whole hops. A rule of thumb is to dry hop near 70 °F (21 °C) in a fermenter.

Just remember that the hops you dry hop with must be absolutely the freshest possible. Any bad or off-flavors you smell in your hops will end up in your beer. So, if your hops smell cheesy or like an old gym bag (both signs of oxidation), toss them — in the garbage, that is, not in your beer!